Analysis of circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) in cancer patients

By Associate Professor Mirette Saad

Published September 2022

Precision medicine in cancer

Cancer, a leading cause of mortality, is associated with aberrant genes. Today, molecular profiling is a recognised technique for classifying solid tumours. Analysis of tumour-associated genetic alterations is increasingly used for diagnostic, prognostic and treatment purposes.

Genetic biomarkers guide treatment decisions

Genetic variants identified in cancer are known to be associated with increased or decreased sensitivity to targeted therapy, such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). For example, while PIK3CA and EGFR mutations are sensitive to TKIs, RAS and BRAF are known to be resistant. Thus, elucidating the genetic profile of a given tumour is potentially useful in designing tailored treatment regimens that avoid unnecessary toxic therapy or overtreatment.

Circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA); Liquid Biopsy

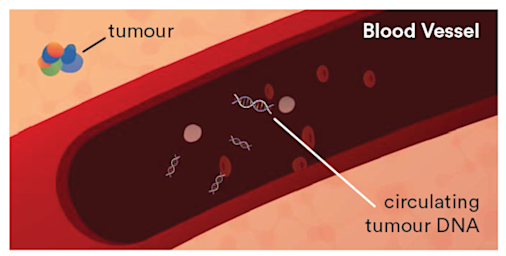

Clinical application of liquid biopsies (Figure 1), to inform molecular-based risk stratification and guide therapeutic intervention strategies, may help to reduce morbidity, increased waiting times and overall costs.

Figure 1. Circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) in a patient with cancer.

ctDNA; A highly specific cancer biomarker

The analysis of ctDNA has already improved clinical outcomes across some cancer types, such as non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), colorectal and breast cancer.

The detection of circulating DNA has been observed by qualitative and quantitative changes. ctDNA has a short half-life allowing for evaluation of tumour changes in hours rather than weeks to months. Studies describe the relationship between ctDNA levels and prognosis and disease stage with a positive predictive value of approximately 94% in NSCLC.

Aspect Liquid Biopsy (LB) Testing at Clinical Labs

Recent technological advances have enhanced the performance of ctDNA analysis, with reported sensitivities and specificities ranging from 90%-100%. Clinical Labs has validated different comprehensive mutation profiling assays for clinical oncology patients using ctDNA extracted from patients’ blood. Our technology, including Next Generation Sequencing (NGS), MassArray Agena Biosciences UltraSEEK and Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR), can indentify clinically relevant variants, with high concordance to solid tissue, at a sensitivity down to 0.5% or less.

ctDNA is highly concordant with Solid Tissue Biopsy

ctDNA analyses demonstrated high concordance to solid tissue tumours (Bettegowda et al., 2014). LB can reveal important information on genomic aberrations affecting the efficacy of targeted drugs, including mutations of the EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, TP53 and PIK3CA genes in different cancers. The variability of ctDNA levels in cancer patients likely correlates with tumour burden, stage, vascularity, cellular turnover and response to therapy.

Liquid Biopsy, the quality approach in a less invasive test

Liquid biopsy offers a clear advantage for some cancer patients compared to conventional surgical methods, particularly for cancers where obtaining repeated tumour biopsies is challenging or unsafe. ctDNA testing has proven value and may replace traditional tissue biopsies in some cases. This non-invasive type of LB can be taken easily and repeatedly over the course of a patient’s treatment.

ctDNA provides broader information with less bias

Studies have revealed that ctDNA provides a more holistic view of tumour characteristics and progression emanating from primary and metastasised tumour foci. ctDNA LB is not biased by analysing only a small fraction of the tumour, which may fail to detect certain clinically relevant alteration types (false negative), and is always accessible, in contrast to lung cancer tissue, for example.

ctDNA analysis is recommended by guidelines in NSCLC

Along with many international guidelines, Australian recommendations and NCCN guidelines were developed to test for resistance T790M EGFR mutations using plasma ctDNA testing in NSCLC if available, followed by a guided tissue biopsy (if feasible) if blood results are negative or indeterminate. Recently, a third-generation EGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor (TKI) was approved in Australia for patients with NSCLC harbouring the EGFR T790M mutation (~50-60% of lung cancer patients), following progression on an EGFR TKI.

The quality choice for monitoring tumour burden and therapeutic response

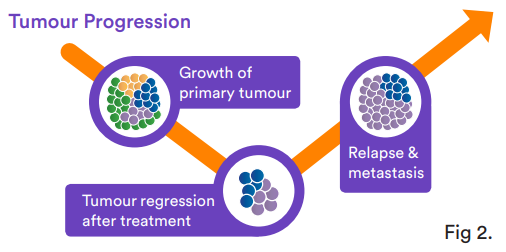

Serial analysis of ctDNA from the time of diagnosis throughout treatment can provide a dynamic picture of molecular disease change, including drug response and development of secondary resistance (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Tumour progression pathway

Similar to lung cancer, plasma-Seq analysis of ctDNAs reveals a wide variety of mutations or aberrations that act as predictive resistance markers against therapies in various forms of cancer. For instance, KRAS, NRAS and BRAF-associated mutations in plasma ctDNA of metastatic colorectal cancer (CRC) patients drive primary resistance five to six months post-anti-EGFR regimens such as panitumumab and cetuximab. Liquid biopsy can be used to assess patient outcome with the addition of a specific PI3K inhibitor to standard treatment for PIK3CA-mutated breast cancer.

Liquid biopsy predicts the clinical outcome and minimal residual disease (MRD)

The clinical utility of ctDNA analysis is demonstrated through the detection or changing levels of ctDNA several weeks after curative surgery or chemotherapy. This could potentially identify patients with residual disease, which can be associated with shorter overall survival (OS) and predict future relapse. Undetectable ctDNA levels at baseline or undetectable ctDNA during the first 6–9 weeks was correlated with prolonged progression-free survival (PFS) and OS in melanoma patients treated with anti-PD1 therapy (Seremet et al., 2019).

ctDNA and real-time monitoring for early relapse

The biggest advantage of LB is the ability to detect cancer biomarkers in blood earlier than conventional methods. It has been demonstrated that monitoring for tumour-derived DNA in plasma can identify relapse well before clinical signs and symptoms appear (~6.5 months earlier than with CT imaging), enabling earlier intervention and better outcomes. Liquid biopsy analysis by NGS detected the presence of a ctDNA PIK3CA mutation five months earlier than the detection of a tumour relapse with multiple liver metastases by regular clinical follow-up in breast cancer (Cheng et al., 2019).

In the future, instead of extensive imaging and invasive tissue biopsies, employing ctDNA as liquid biopsies could be used to guide cancer treatment decisions and perhaps even screen for the recurrence of tumours that are not yet visible on imaging.

Liquid biopsy and cancer screening

The non-invasive nature of LB represents an advantage over other approaches to define cancer biomarkers, particularly for the development of cancer screening tests. Despite the myriad of benefits, the potential of using liquid biopsy as a screening tool is still evolving.

Conclusion

The present literature supports the validity of LB as a minimally invasive diagnostic tool for monitoring therapeutic response and the detection of novel cancer driver mutations, this can enable earlier detection of tumour burden, long before conventionally-utilised tests.

If you enjoyed this article, subscribe to our electronic Pathology Focus newsletter.

References

Bettegowda, C., et al., 2014 Chakrabrti, S., et al., 2020 Cheng, F.T.-F., et al., 2020 Haselmann, V., et al., 2018 Hirahata, T., et al., 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Non-small cell lung cancer (7 April 2017) Pessoa, L.S., et al., 2020 Pavlakis, N., et al., 2017. Cancer Council Australia Lung Cancer Guidelines Working Party. What is the Optimal First-line Maintenance Therapy for Treatment of Stage IV Inoperable NSCLC? Ramalingam, S.S., et al., 2020 Rolfo, C., et al., 2020 Russo, A., et al., 2020 Remon, J., et al., 2020 Seremet, T., et al., 2019 Wang, W., et al., 2017 Wu, J., et al., 2020 Yoshinami, T., et al., 2020